The Legend of Charles Baudelaire

James Huneker (1857-1921) was an American art, literary, music and theater critic. Here is a preface that he wrote in “The Poems and Prose Poems of Charles Baudelaire” (1919) concerning the legendary dissipation of Charles Baudelaire and others.

For the sentimental no greater foe exists than the iconoclast who dissipates literary legends. And he is abroad nowadays.

Those golden times when they gossiped of De Quincey’s enormous opium consumption, of the gin absorbed by gentle Charles Lamb, of Coleridge’s dark rays, Byron’s escapades, and Shelley’s atheism— alas! into what faded limbo have they vanished.

Poe, too, whom we saw in fancy reeling from Richmond to Baltimore, Baltimore to Philadelphia, Philadelphia to New York. Those familiar fascinating anecdotes have gone the way of all such jerry-built spooks. We now know Poe to have been a man suffering at the time of his death from cerebral lesion, a man who drank at intervals and little. Dr. Guerrier of Paris has exploded a darling superstition about De Quincey’s opium-eating. He has demonstrated that no man could have lived so long— De Quincey was nearly seventy-five at his death— and worked so hard, if he had consumed twelve thousand drops of laudanum as often as he said he did. Furthermore, the English essayist’s description of the drug’s effects is inexact. He was seldom sleepy— a sure sign, asserts Dr. Guerrier, that he was not altogether enslaved by the drug habit. Sprightly in old age, his powers of labour were prolonged until past three-score and ten. His imagination needed little opium to produce the famous Confessions. Even Gautier’s revolutionary red waistcoat worn at the premiere of Hernani was, according to Gautier, a pink doublet. And Rousseau has been whitewashed. So they are disappearing, those literary legends, until, disheartened, we cry out: Spare us our dear, old- fashioned, disreputable men of genius!

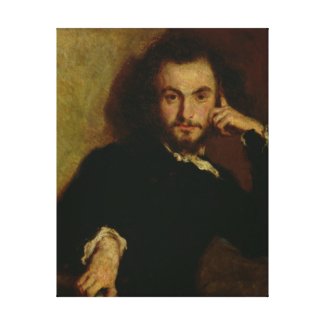

But the legend of Charles Baudelaire is seemingly indestructible. This French poet has suffered more from the friendly malignant biographer and chroniclers than did Poe. Who shall keep the curs out of the cemetery? asked Baudelaire after he had read Griswold on Poe. A few years later his own cemetery was invaded and the world was put into possession of the Baudelaire legend; that legend of the atrabilious, irritable poet, dandy, maniac, his hair dyed green, spouting blasphemies; that grim, despairing image of a diabolic, a libertine, saint, and drunkard. Maxime du Camp was much to blame for the promulgation of these tales— witness his Souvenirs litteraires. However, it may be confessed that part of the Baudelaire legend was created by Charles Baudelaire. In the history of literature it is difficult to parallel such a deliberate piece of self-stultification.

Not Villon, who preceded him, not Verlaine, who imitated him, drew for the astonishment or disedification of the world a like unflattering portrait. Mystifier as he was, he must have suffered at times from acute cortical irritation. And, notwithstanding his desperate effort to realize Poe’s idea, he only proved Poe correct, who had said that no man can bare his heart quite naked; there always will be something held back, something false ostentatiously thrust forward. The grimace, the attitude, the pomp of rhetoric are so many buffers between the soul of man and the sharp reality of published confessions. Baudelaire was no more exception to this rule than St. Augustine, Bunyan, Rousseau, or Huysmans; though he was as frank as any of them, as we may see in the printed diary, Mon coeur mis a nu (Posthumous Works, So-cidt6 du Mercure de France); and in the Journal, Fusees, Letters, and other fragments exhumed by devoted Baudelarians.

To smash legends, Eugene Crepet’s biographical study, first printed in 1887, has been republished with new notes by his son, Jacques Crepet. This is an exceedingly valuable contribution to Baudelaire lore; a dispassionate life, however, has yet to be written, a noble task for some young poet who will disentangle the conflicting lies originated by Baudelaire— that tragic comedian— from the truth and thus save him from himself. …

In November 1850, Maxime du Camp and Gustave Flaubert found themselves at the French Ambassador’s, Constantinople. The two friends had taken a trip in the Orient which later bore fruit in Salammbo. General Aupick, the representative of the French Government, cordially the young men received; they were presented to his wife, Madame Aupick. She was the mother of Charles Baudelaire, and inquired rather anxiously of Du Camp: “My son has talent, has he not?” Unhappy because her second marriage, a brilliant one, had set her son against her, the poor woman welcomed from such a source confirmation of her eccentric boy’s gifts. Du Camp tells the much-discussed story of a quarrel between the youthful Charles and his stepfather, a quarrel that began at table. There were guests present. After some words Charles bounded at the General’s throat and sought to strangle him. He was promptly boxed on the ears and succumbed to a nervous spasm. A delightful anecdote, one that fills with joy psychiatrists in search of a theory of genius and degeneration. Charles was given some money and put on board a ship sailing to East India. He became a cattle-dealer in the British army, and returned to France years afterward with a Venus noire, to whom he addressed extravagant poems! All this according to Du Camp.

Here is another tale, a comical one. Baudelaire visited Du Camp in Paris, and his hair was violently green. Du Camp said nothing. Angered by this indifference, Baudelaire asked: “You find nothing abnormal about me?” “No,” was the answer. “But my hair ? it is green!” “That is not singular, mon cher Baudelaire; every one has hair more or less green in Paris.” Disappointed in not creating a sensation, Baudelaire went to a cafe, gulped down two large bottles of Burgundy, and asked the waiter to remove the water, as water was a disagreeable sight; then he went away in a rage. It is a pity to doubt this green hair legend; presently a man of genius will not be able to enjoy an epileptic fit in peace— as does a banker or a beggar. We are told that St. Paul, Mahomet, Handel, Napoleon, Flaubert, Dostoievsky were epileptoids; yet we do not encounter men of this rare kind among the inmates of asylums. Even Baudelaire had his sane moments.

Recent Comments